Why Bitch Spays Are Such A Bitch

It’s ironic that one of the most common surgeries that veterinary surgeons are asked to do is also one of the most complex: bitch spays. There’s only one occasion in my life when I have witnessed a vet fleeing the operation theatre in floods of tears, and that was when I was a student watching a young vet carry out a challenging deep chested bitch spay. Another vet had to be called in to finish the operation that day. Until then, I had assumed that this standard operation was simple. On that day, I learned that this was a surgery that needed skill, perseverance and sometimes, courage.

There are three main challenges to bitch spays;

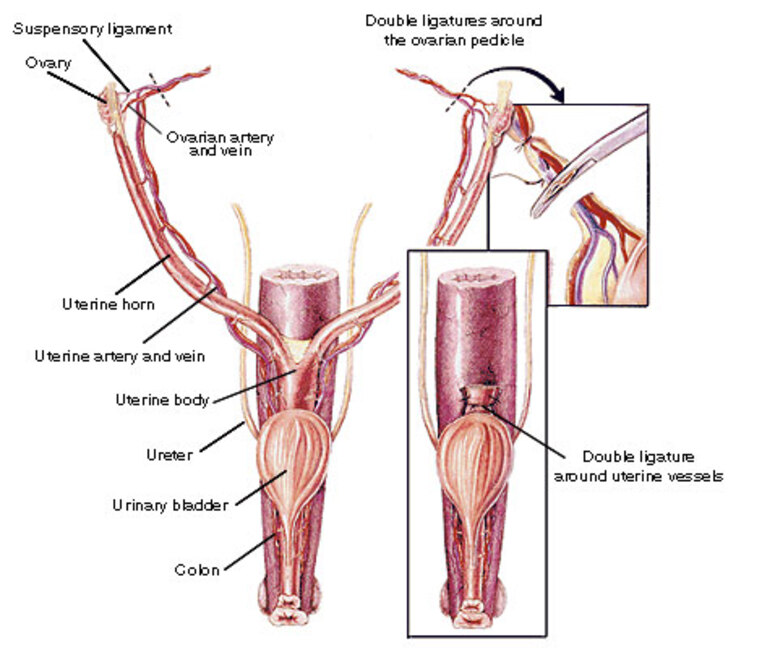

First, the organs to be removed are attached deep inside the dog’s body. While it’s easy enough to expose and tie off the cervix, the ovaries are located high up in the abdomen, close to the kidneys. It can be difficult to reach them, mobilise them and tie them off. There’s always a fear that their attachment, including the blood vessels, will tear, causing a major bleed. In fact, it’s rare for that to happen, and when it does (as it did to my tearful colleague), you have to stay calm and logical while you find and tie off the bleeding vessels. But if you don’t have previous experience of having this happen, it can be highly stressful and even frightening.

The second challenge is that if an animal is obese (as many are), the excess fat in the abdomen creates a fog-like lack of visibility during surgery. It can be surprisingly difficult to find the uterus and ovaries, and it can be tricky to mobilise them adequately and to tie off the blood vessels effectively.

The third challenge is the “bleeder”. All vets who’ve done more than a dozen bitch spays will know what I mean. This is when you have completed the op, carefully and securely tying off all blood vessels that have been cut, and for no obvious reason, blood starts to seep from somewhere. This can happen before you have closed the abdomen, or worse again, it can happen when the operation has finished: the animal has woken up, and is in the recovery stage when blood starts to drip from the incision site. This type of scenario presents a challenge for vets. Ideally, there should be absolutely no bleeding from a surgical wound and that is always the goal.

It’s easier when you have not yet closed the abdomen: you can go back to the main blood vessels, double checking that they are securely and effectively ligated. This is usually the case: the bleeding is often from minor blood vessels in the broad ligament. Extra ligation of these may be needed, or ideally, the use of a cautery system during surgery will prevent them from causing a problem in the first place.

But what about the animal whose operation has been completed? Is the ooze of blood copious enough to require another general anaesthetic and a second invasive surgery? Or is it just a minor trickle of blood, due to minor blood vessels in the skin, muscle or abdomen which will seal over naturally after a short period of time? This can be a difficult judgment call: often a body bandage is all that’s needed, applying pressure to the wound to aid in clotting. But I remember cases where I have not been certain that this is the right course of action, and I’ve worried as I’ve continued to monitor the case, repeatedly checking the packed cell volume to reassure myself that the bleeding is minor.

The good news is that we vets have all undergone careful and rigorous training in surgery, and while we may feel anxious when we experience any sort of complication like this, we do know how to deal with such situations safely.

The truth is that some bitch spays will always be a bitch.

Perhaps the only consolation is that when you can truly master the bitch spay, you have proven that you are a competent soft tissue surgeon. There are very few operations that are as complex as a tricky ovario-hysterectomy.