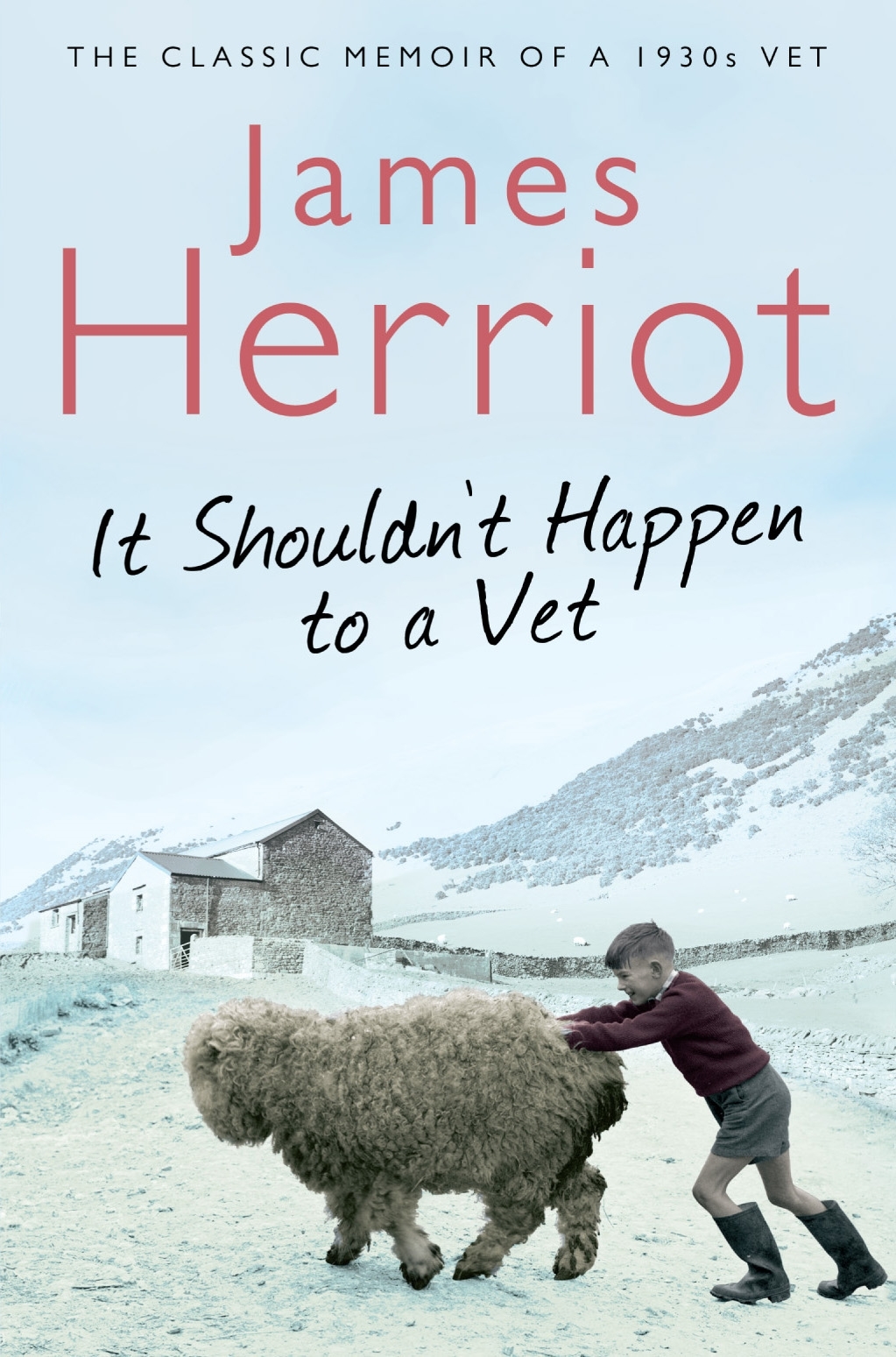

James Herriot, the pen name of Scottish vet Alf Wight, must have single-handedly influenced more vets than any other individual. Sadly, he died from cancer in 1995 at the age of 78, but if he had still been alive, he would have been a hundred years old last month. His books – about the vagaries of veterinary practice in the Yorkshire Dales – sold millions. The BBC television series “All Creatures Great and Small”, based on his books, was equally successful, with over ninety episodes between 1978 and 1990. Even today, the programmes can be watched on cable television channels, and they’re as enjoyable as ever.

James Herriot, like many vets, loved his work but he also suffered from the stresses of the job. He started to write relatively late in life, at the age of 53, when recovering from clinical depression, His stories were a combination of idyllic descriptions of mixed practice in the Yorkshire Dales, self-deprecating tales of the challenges he faced, interspersed with humorous accounts of some of the funnier aspects of a vet’s life.

I was in my early teens when Herriot’s books were published: I’d already decided that I wanted to be a vet, but his endearing tales confirmed for me that this was definitely how I wanted to spend my life.

Life never works out quite as planned, and as it turned out, the reality of life in James Herriot style mixed practice didn’t suit me as well as I’d expected. After five years of farm, equine and small animal work in a rural part of Scotland, I realised that the veterinary world had changed. It was increasingly difficult to be competent at everything, and the expectations of our clients were high. I ended up focusing on small animal work in a suburb: my Herriot-loving teenage self would have been surprised, but it has suited me well. I still enjoy rural life, but just in my off-duty time, walking, running and cycling in the countryside rather than while working.

Funnily enough, although my job is very different to Herriot’s, the events that I experience in practice are often very similar. The main focus of his work was animals, and their relationships with humans, and that’s still what makes up most of my daily work.

Herriot wrote about Mrs Pumphrey, with her pampered Pekingnese, Tricki-Woo. Like most vets, I have many similar clients who molly-coddle their pets to extreme degrees, and just as Herriot was “Uncle James”, so I am “Uncle Pete”.

He wrote about grumpy farmers who made his life difficult; as a small animal vet, I have my share of challenging owners who force me to extend myself to be more diplomatic, polite and tolerant than I might feel like being at the time.

Herriot wrote about cases that baffled him, about animals that made miraculous recoveries, and about others that failed to survive, despite his best efforts. I too have these experiences: they are a universal part of being a vet in any type of clinical practice.

Finally, James Herriot wrote about individual animals that caught his attention: cows, horses, pigs, sheep, dogs and cats. He wrote about their personalities, their peculiarities, their likes and dislikes. Similarly, I am privileged to get to know a wide range of animals, although over a narrower range of species. Some of them even become “friends”, in that I know them, enjoy their company and am very happy to spend time with them.

James Herriot wrote spectacularly well about life as a vet. Many others have tried to emulate him, but he was such an accomplished master of the pen that to date, nobody has managed to achieve similar far reaching success with their books. Will there be a James Herriot of the twenty first century, someone who writes lucidly and engagingly about the veterinary career of today? If so, I look forward to reading his – or her – books in due course.